Research

The Cell as an “Organic Architecture”

Cells are exquisite architectural creations of nature. Within each cell, diverse components — molecules, cytoskeletal elements, and organelles — interact with one another to generate intricate and flexible spatial order, all without a central designer or architect. We regard this as a prime example of organic architecture, and the study of its underlying mechanisms forms the basis of what we call Cell Architectonics [1]. In 2006, we established the Cell Architecture Laboratory at the National Institute of Genetics (NIG) to explore and develop this new field.

The ordered structures within cells are directly linked to their functions. Understanding how a cell is “constructed” can shed light not only on fundamental processes such as cell growth and movement, but also on the organization of our own bodies — and even on the principles that shape societies and cities. Observing cells reveals the hidden harmony between life and structure, offering insights that may inspire the designs of the future.

[1] For further details, see Quantitative Biology – A Practical Introduction by Akatsuki Kimura (Springer Nature Singapore, 2022).

Architecture of a Single Cell: Unraveling the Laws of Force and Organization

Our bodies are composed of countless cells. Each cell is the smallest unit of life and can live independently. Yet, a cell is far more than a mere collection of chemicals. Its molecular components — such as proteins and the cytoskeleton — are precisely arranged and dynamically reorganized over time, enabling the activities we recognize as life. This is much like how a house becomes livable only when its parts are assembled in the right way, or how a city becomes vibrant through the flow of people and materials. In this sense, a cell is a living architecture, where molecular components collectively create their own spatial order.

Such phenomena, in which order emerges spontaneously without an external designer, are known as self-organization. Understanding how cells achieve self-organization is key to uncovering the fundamental principles of life itself.

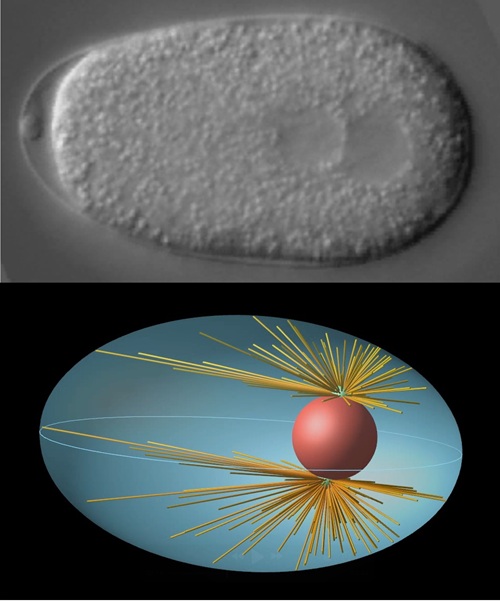

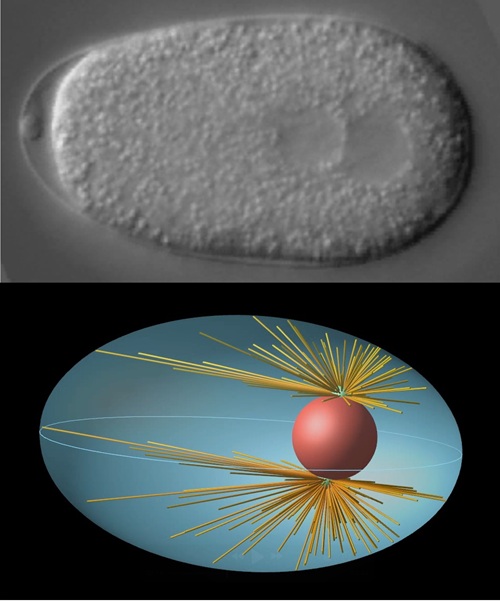

Since its foundation, the Cell Architecture Laboratory has focused on the one-cell embryo of Caenorhabditis elegans as a model system to explore the physical mechanisms of self-organization. By combining quantitative microscopy with theoretical modeling based on mechanics, we have revealed how the cell nucleus is positioned at the cell center [2], and how cytoplasmic streaming is initiated and reverses direction[3]. Through these studies, we have gained a universal insight: robust intracellular organization can arise from a simple balance between molecular interactions and physical forces.

Selected Publications

[2] Kimura K & Kimura, PNAS 2011; Tanimoto et al, J Cell Biol 2016; Goda et al, PNAS 2024

[3] Niwayama et al, PNAS 2011; Kimura K et al, Nat Cell Biol 2017; Ishikawa et al, PRX Life 2025

Multicellular Architecture: Physical Principles Hidden in Diversity

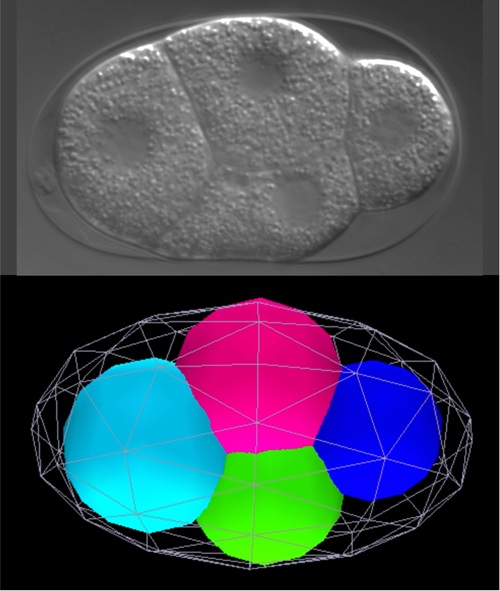

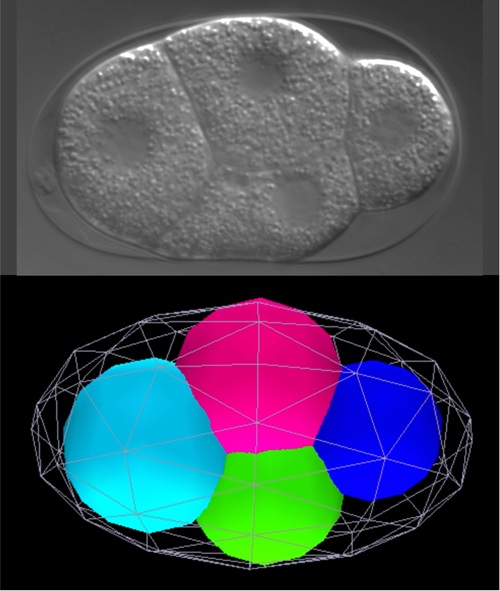

Building on our understanding of single-cell organization, we are now tackling one of the most fundamental questions in biology — embryonic development. During the early stages of embryogenesis, repeated cell divisions produce progressively smaller cells, resulting in a coexistence of cells of various sizes. While developmental biology has traditionally emphasized genetic programs, we add another crucial perspective: the role of physical constraints.

We investigate how physical properties — such as cell and nuclear size [4], surface tension and cytoplasmic viscoelasticity — influence diverse processes, including chromosome dynamics [5], intracellular transport [6], multicellular arrangement [7], and ultimately tissue morphogenesis and the timing of gene expression. Our overarching goal is to understand whether the formation of such diverse cellular societies can, in the end, be explained by a small set of universal physical principles.

Selected Publications

[4] Hara & Kimura, Curr Biol 2009

[5] Yesbolatova et al, Phys Rev Lett 2022

[6] Torisawa et al, bioRxiv 2024

[7] Yamamoto & Kimura, Development 2017; Seirin-Lee et al, Development 2022.

Caenorhabditis elegans— Our Research Partner

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a tiny animal, only about 1 mm in length, yet it is one of the most important model organisms in modern biology. It is used across a wide range of disciplines — from physiology and developmental biology to behavior and ecology. As Dr. Sydney Brenner, who pioneered C. elegans research, once wrote:

“with a few toothpicks, some petri dishes and a microscope, you can open the door to all of biology.” (Foreword to C. elegans II)

Indeed, C. elegans offers profound insights into the complexity of life through an elegantly simple experimental system. Its cell divisions and differentiations proceed with remarkable reproducibility, and its transparent body allows direct observation of living processes — making it an ideal organism for studying cell architecture. For us, C. elegans is not just a model organism, but truly a partner in discovery [8].

[8]Link:The website of a community of Japanese nematode researchers

Early Embryogenesis of C. elegans

This video shows the development of a C. elegans embryo — from a single fertilized egg undergoing repeated cell divisions to forming the shape of a larva. The entire process spans about 450 minutes, here played at 900× speed (the egg is approximately 0.05 mm in size). The round structures visible are cell nuclei, which increase in number with each division. What begins as a simple cluster of cells gradually becomes organized and starts to take on the characteristic form of the nematode — offering a glimpse into the very moment when life takes shape.

First Cell Division of C. elegans

This video captures the very first cell division that occurs after fertilization, observed over 20 minutes and played here at 100× speed. On the left side of the egg is the maternal nucleus, and on the right is the paternal nucleus. When these two nuclei meet and fuse, a new nucleus — the genetic center of a new individual — is formed. Soon after, the cell divides into two, but the division is asymmetric: the left cell is larger, while the right one is smaller. Through this asymmetric division, the two cells begin to acquire distinct identities — marking the very first step in their separate journeys, despite sharing the same origin.

Chromosome Segregation During Cell Division in C. elegans

This video shows how chromosomes are accurately distributed during cell division, captured using fluorescence microscopy. By labeling both the chromosomes and the fine thread-like structures that pull them apart — the cytoskeletal fibers — we can visualize the intricate mechanism of mitosis.

The bright, thread-like structures in the center are chromosomes, which are pulled to opposite sides by fibers extending from both poles. Together, the chromosomes and fibers form a diamond-shaped structure called the spindle apparatus, an essential machine that ensures genetic information is faithfully transmitted to the next generation of cells.

Measuring and Modeling

With the progress of genome analysis and high-throughput data acquisition, we now live in an era surrounded by vast amounts of biological information. Advances in imaging technologies have made it possible to obtain precise quantitative data, and as we tackle increasingly complex biological phenomena, quantification and computation have become more essential than ever [9].

However, collecting and quantifying data alone is not enough. No matter how large the dataset, we cannot fully understand how the pieces fit together to form a functioning system simply by looking at the numbers. What we need are models.

A “model” in this context is a simplified representation that captures the essential features of a biological process. Just as a map represents a real city in reduced form, a model serves as a guide for understanding how cells behave. By constructing models, we can test questions such as “What happens if this molecule stops functioning?” or “How does changing the magnitude of a force alter the behavior?” Comparing the model’s quantitative behavior with real data then allows us to uncover patterns and principles that intuition alone could not reveal.

In our research, we often use four-dimensional models — that is, models that incorporate the three dimensions of space plus time. Because cellular behavior changes dynamically, capturing its temporal evolution is crucial for understanding it properly.

The first role of a model is to reproduce observed phenomena and help us grasp their underlying mechanisms. Yet, building a model often exposes unexpected challenges: Which molecular components must be considered to explain a movement? How can we estimate the magnitude of forces involved? Through this process, we realize what we know — and, more importantly, what we do not know. This awareness of our own ignorance becomes a powerful driver for new questions and new discoveries.

Moreover, modeling is also a way of expressing scientific results. Leonardo da Vinci, both an artist and a scientist, created anatomical sketches and studies of perspective that arose from the mutual influence of scientific inquiry and artistic expression. Our four-dimensional models play a similar dual role: they are tools for scientific exploration, helping us understand phenomena, and at the same time means of expression, conveying the beauty and dynamics of life in a form that can be intuitively felt.

[9]For a practical introduction to quantitative methods related to cell architecture, see Quantitative Biology–A Practical Introduction by Akatsuki Kimura (Springer, Singapore 2022).